CRDTs for Collaborative Writing

An introduction to Conflict-Free Replicated Data Types

Init Journey and Journal

These past months I’ve been helping out with technical screen interviews on the job, the regular 1-hour meeting in which the candidate is given a code challenge and must provide a decent working solution by the end of it.

Surprisingly enough, the place I work at does not provide access to any interview platform to assess the candidate’s skills, leaving me in a tight spot. From time to time, I have to request them to open the IDE of their choice and kindly share the screen, which I found invasive and likely to reduce the formality of the process.

Nowadays, there is a wide variety of paid services online such as CoderPad, CodeInterview, HackerRank, CoderByte; To mention a few, and all of them offer robust capabilities for online interviews.

Similarly, on the side of free software, we have etherpad, collabedit, and Plunker. These last ones have been an experience-saver when the candidate cannot share the screen for any reason, yet, these reflect intermittent issues lke edit-lag from time to time.

That situation got me intrigued and oddly inspired. How do all these real-time collaborative text platforms operate? What is the engineering behind it? Which type of technical challenge do they face, and which approaches do they follow?

Those are plenty of questions, right? Here is where I start my amateur research on this particular topic: collaborative text in distributed systems.

Collaborative Text: How does it work?

Collaborative text web applications are asynchronous, fully powered by distributed systems, and challenged by their complexity. Consistency in the operations executed by the users takes the primary seat, while they are directly affected by the latency between the nodes.

If two users write, update or delete the same word in the document. Which change is the right one? Is it the last one? Is it the first one? How do we handle this edit conflict?

In an article published in 2011 by Marc Shapiro, Nuno Preguiça, Carlos Baquero, and Marek Zawirski named “A comprehensive study of Convergent and Commutative Replicated Data Types.”1 they propose the design of shared data types capable of conflict-free eventual consistency.

Quoting the Abstract:

Eventual consistency aims to ensure that replicas of some mutable shared object converge without foreground synchronisation. Previous approaches to eventual consistency are ad-hoc and error-prone. We study a principled approach: to base the design of shared data types on some simple formal conditions that are sufficient to guarantee eventual consistency. We call these types Convergent or Commutative Replicated Data Types (CRDTs). (2011) 1

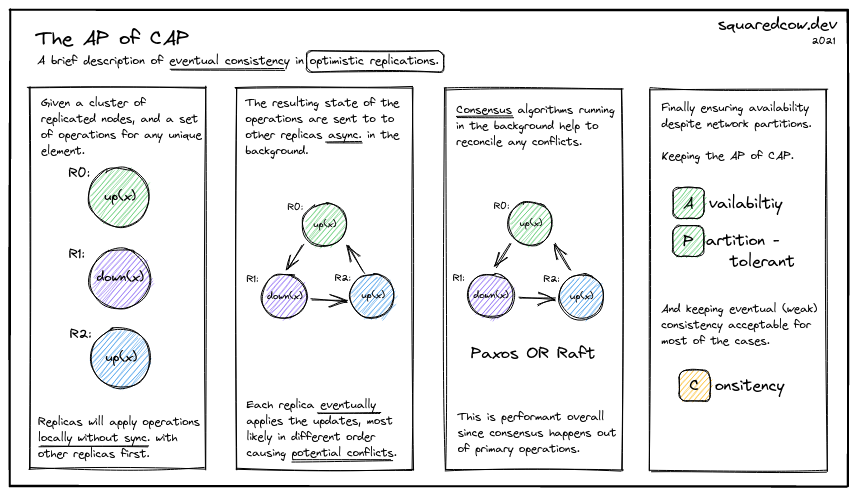

The infographic below displays an understandable glimpse of eventual consistency in optimistic replications. We will need at least this explanation as our bare minimum context to keep moving forward.

a). The AP of CAP

a). The AP of CAP

Diving into CRDTs

To properly define a CRDT we need to look into the smaller pieces used for their construction and later elaborate on the type of operations they can execute.

The clay and bricks of CRDTs

CRDTs build and operate with mutable and immutable data types. The immutable types are named atoms, and they hold characteristics, such as:

- Their content determines the type, e.g., primitives.

- They are copiable in between processes.

- If two of them have the same contents, they are equal.

Meanwhile, the mutable types are named objects and have different characteristics than atoms, such as:

- They hold identity and initial state.

- The contents of an object, also known as payload, are conformed by any number of atoms or objects.

- They expose an interface that defines contractual operations on the object.

- They are replicable in between processes.

- If two objects have the same identity but are present in different processes, they are considered replicas.

The operations exposed for working with objects may follow two different approaches: state-based and operation-based.

Categories of CRDTS

In state-based (passive) replication, every state-changing operation occurs at the source then the system propagates the modified payload to an arbitrary pair of replicas infinitely often. The CRDTs implementing a state-based approach are named Convergent Replicated Data Type, CvRDTs.

Meanwhile, in operation-based (active) replication, the system transmits the state-changing operations in two phases: at-source (local) and downstream (async. in replica) one after the other, and both of them must execute atomically. The CRDTs implementing an operation-based strategy are named Commutative Replicated Data Type, CmRDTs.

Now, let’s have a quick grasp of one of the basic CvRDTs next.

Building basic CRDTs

Counters

The most basic of the CRDTs, a primitive that lives within the replicas exposing a set of basic operations:

- Increment/decrement the value of the counter.

- Update the value of the counter.

- Query the value of the counter.

The value of the primitive must converge towards the global number of increments minus the number of decrements. These are some of the defined CRDTs counters 1:

- Grow-only Counter (G-Counter): state-based counter for positive increments only.

- Positive-Negative Counter (PN-Counter): state-based counter with a double registry for positive and negative increments.

- Non-negative Counter: similar to PN-Counter with the restriction of not beign able to generate more decrements than the current originated increments.

To provide a more thorough view of one the counters mentioned above, we picked G-Counter to further explain its operations.

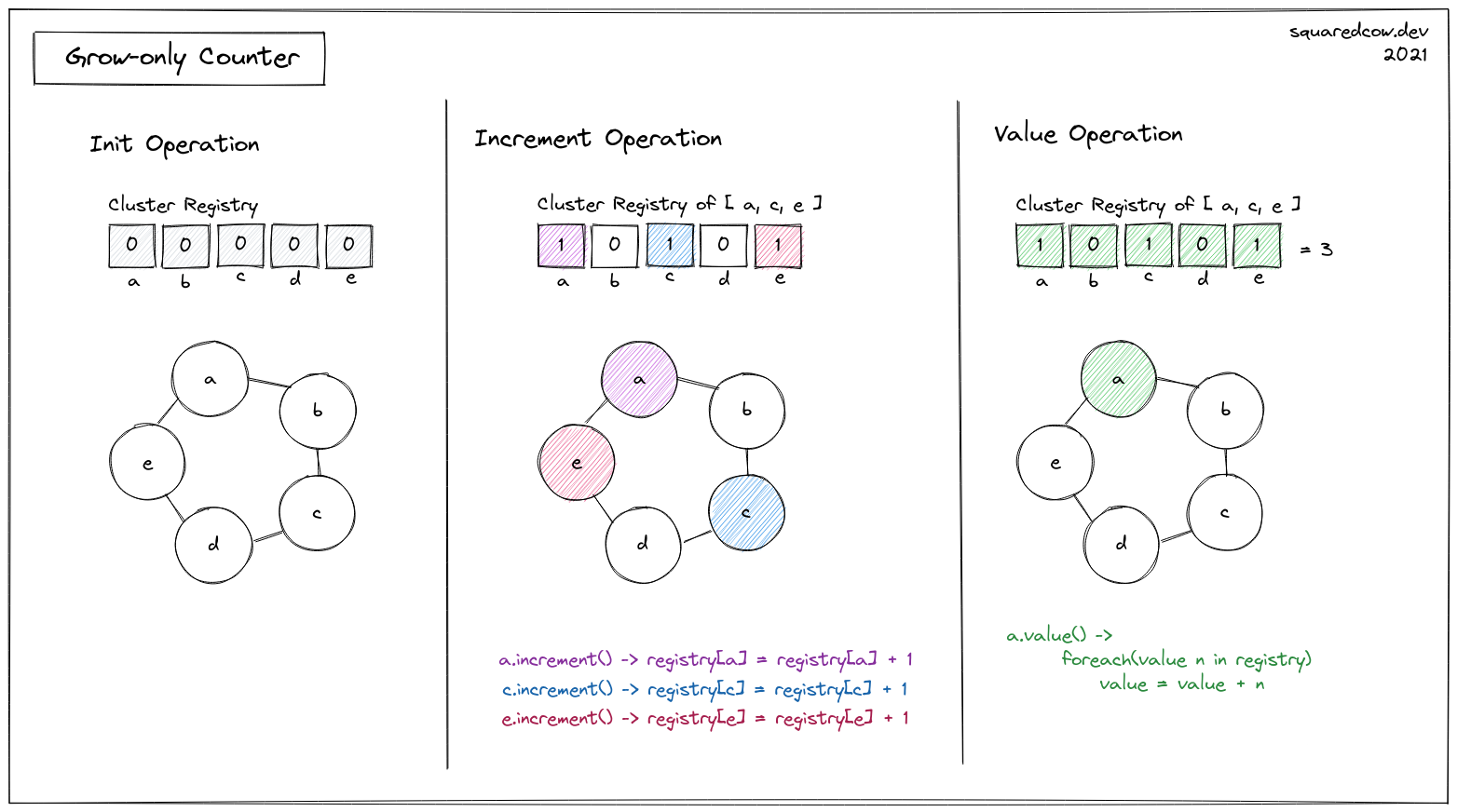

Grow-only Counter (G-Counter)

G-Counter is a state-based CRDT or CvRDT for positive increments only. As mentioned above it exposes a set of basic operations: init, increment, value, merge and compare. 2

b). G-Counter OPS: init, increment and value.

b). G-Counter OPS: init, increment and value.

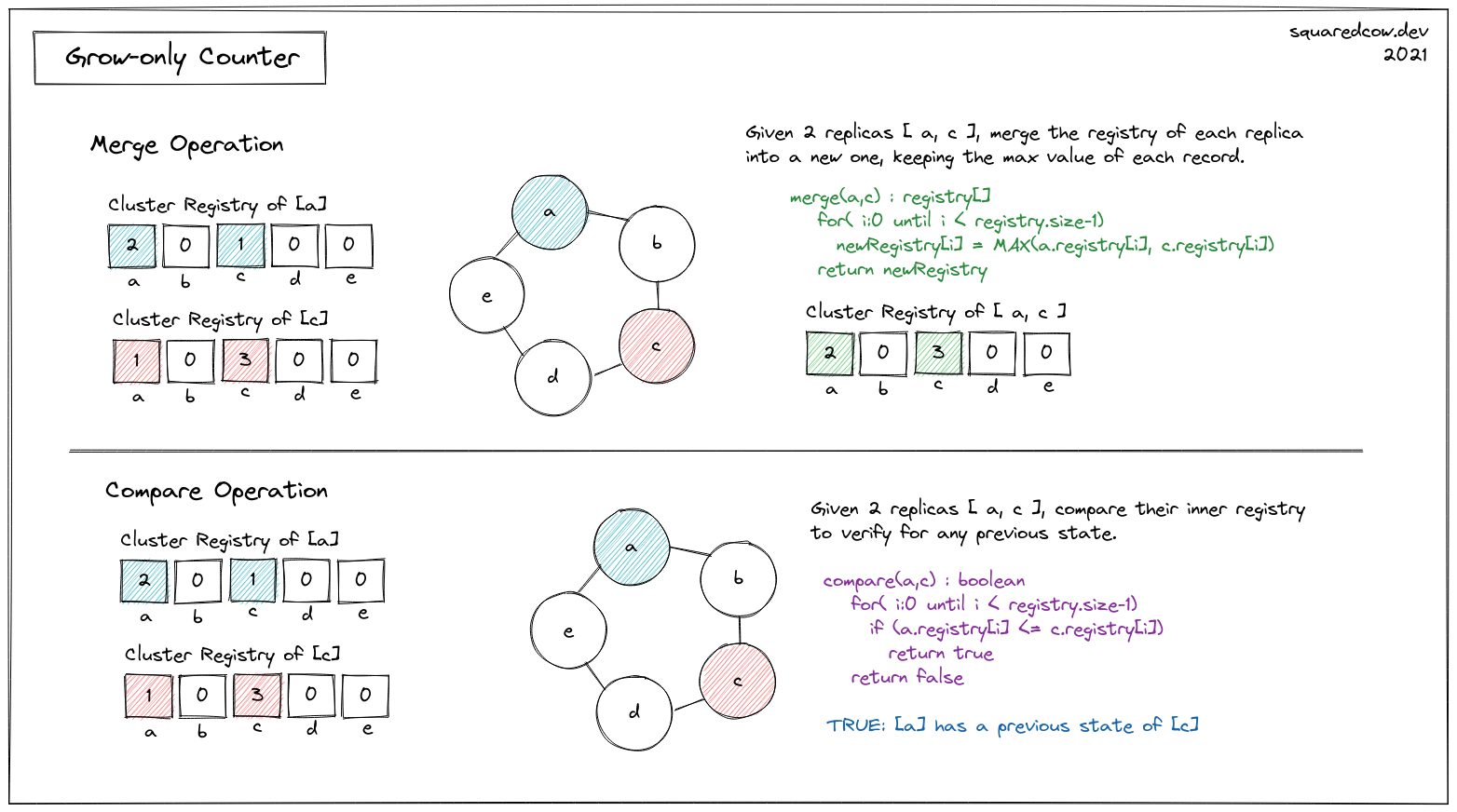

c). G-Counter OPS: merge and compare.

c). G-Counter OPS: merge and compare.

To further visualize a GCounter, we can easily create a class named GCounter that operates with integers and implements each of the methods explained above.

| |

d). GCounter implementation in Java

Closing words and next-steps

This is an initial dive into the CRDTs structures themselves, we will eventually go deeper to construct a cluster of replicas that operate with them. We still need to go first through the rest of the structures mentioned, such as: registers, sets and graphs, but let’s have those on a second entry on this blog series.

With nothing left to add, thank you for reading all the way through, until next time.

– squaredcow

https://hal.inria.fr/inria-00555588/document Shapiro, Marc; Preguiça, Nuno; Baquero, Carlos; Zawirski, Marek (13 January 2011). “A Comprehensive Study of Convergent and Commutative Replicated Data Types”. Rr-7506. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conflict-free_replicated_data_type Section: Known CRDTs ↩︎